The MSCOS is designed for adult survivors, however we have partnered with the MSCOS equivalent for children, "Creating Stable Futures: Human Trafficking, Participation and Outcomes for Children" and the existing model of our MSCOS partner Emma Howarth from University of East London. It is essential that no gaps are left for children and young people – including the many who are wrongly age-disputed by the authorities and believed to be adults, those who are highly vulnerable to re-trafficking and further harm but have transitioned from child support into an adult system that has failed them, and those who children at risk of human or the children of survivors. On this page we share some relevant practice models and frameworks for children and young people, which reflect the positive outcomes in Creating Stable Futures: Human Trafficking, Participation and Outcomes for Children.

Relevant Practice Models and Frameworks

|

Creating Stable Futures: Human Trafficking, Participation and Outcomes for Children

This research project aimed to understand what positive outcomes for these young people would look like, and what the pathways towards these positive outcomes might be. It examines how to ensure protection and support for children who have experienced modern slavery. For the first time, young people have identified 25 distinct outcomes as being important and meaningful to them and have contributed to the development of a new ‘Positive Outcomes Framework’ which can be used by practitioners and policymakers when interacting with and supporting young victims of trafficking. The research was led by the Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice at Sheffield Hallam University and the University of Bedfordshire’s Institute of Applied Social Research, in partnership with ECPAT UK (Every Child Protected Against Trafficking). |

|

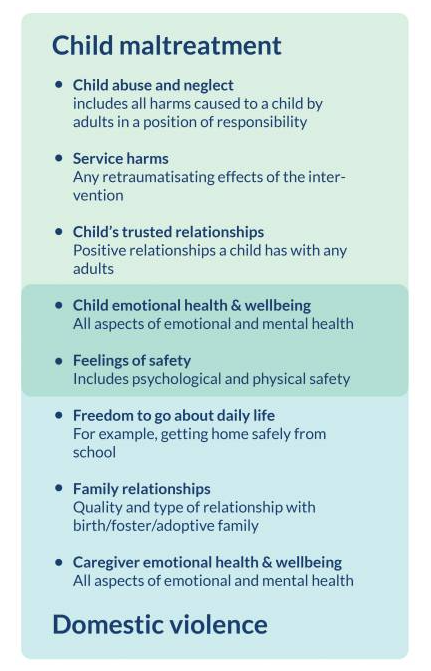

Core outcome sets for family and child-focused interventions

We developed two core outcomes sets that those who use, deliver and commission services agreed were the most important to measure. We involved survivors of violence and abuse and practitioners at every stage of the process. The aim is for the core outcome sets to be reported as a minimum in evaluations of child maltreatment and domestic violence interventions where the child is the focus; this includes interventions delivered to caregivers or other family members. Members of the core outcome set team were funded by the Home Office to review measurement tools that could be used when measuring the domestic violence and abuse core outcomes (DVA-COS). We ran an abridged consensus and review process with an international group of experts to understand which tools they felt were most feasible and acceptable to be used to evaluate child-focused domestic abuse interventions. We found that many tools are not trauma-informed and only one measurement tool met everyone’s criteria. The report can be found here. |

The Lundy Model

Since 2014, the Lundy model of child participation, based on four key concepts (Space, Voice, Audience and Influence), has been used and adopted by national and international organisations, agencies and governments to inform their understanding of children’s participation, generating a sea-change in global understanding of child rights-based participation for both policy and practice.

Article 12 is often described under the banner of 'the voice of the child', ‘pupil voice’ or 'the right to be heard', but these can misrepresent and indeed undermine the rights of children and young people. In view of this, Professor Laura Lundy, drawing on the research for NICCY, proposed a model for rights-compliant children’s participation which offers a legally sound but practical conceptualisation of Article 12 of the CRC. This model suggests that implementation of Article 12 requires consideration of four inter-related concepts:

Since 2014, the Lundy model of child participation, based on four key concepts (Space, Voice, Audience and Influence), has been used and adopted by national and international organisations, agencies and governments to inform their understanding of children’s participation, generating a sea-change in global understanding of child rights-based participation for both policy and practice.

Article 12 is often described under the banner of 'the voice of the child', ‘pupil voice’ or 'the right to be heard', but these can misrepresent and indeed undermine the rights of children and young people. In view of this, Professor Laura Lundy, drawing on the research for NICCY, proposed a model for rights-compliant children’s participation which offers a legally sound but practical conceptualisation of Article 12 of the CRC. This model suggests that implementation of Article 12 requires consideration of four inter-related concepts:

- SPACE: Children must be given the opportunity to express a view

- VOICE: Children must be facilitated to express their views

- AUDIENCE: The view must be listened to.

- INFLUENCE: The view must be acted upon, as appropriate.

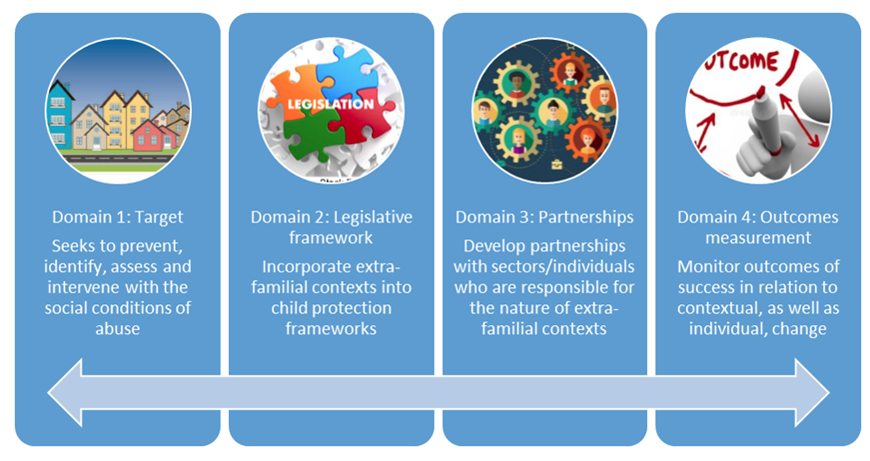

Contextual Safeguarding

Contextual Safeguarding is an approach to understanding, and responding to, young people’s experiences of significant harm beyond their families. It recognises that the different relationships that young people form in their neighbourhoods, schools and online can feature violence and abuse. Parents and carers have little influence over these contexts, and young people’s experiences of extra-familial abuse can undermine parent-child relationships.

Therefore, children’s social care practitioners, child protection systems and wider safeguarding partnerships need to engage with individuals and sectors who do have influence over/within extra-familial contexts, and recognise that assessment of, and intervention with, these spaces are a critical part of safeguarding practices. Contextual Safeguarding, therefore, expands the objectives of child protection systems in recognition that young people are vulnerable to abuse beyond their front doors.

Four domains of Contextual Safeguarding

Contextual Safeguarding is an approach to understanding, and responding to, young people’s experiences of significant harm beyond their families. It recognises that the different relationships that young people form in their neighbourhoods, schools and online can feature violence and abuse. Parents and carers have little influence over these contexts, and young people’s experiences of extra-familial abuse can undermine parent-child relationships.

Therefore, children’s social care practitioners, child protection systems and wider safeguarding partnerships need to engage with individuals and sectors who do have influence over/within extra-familial contexts, and recognise that assessment of, and intervention with, these spaces are a critical part of safeguarding practices. Contextual Safeguarding, therefore, expands the objectives of child protection systems in recognition that young people are vulnerable to abuse beyond their front doors.

Four domains of Contextual Safeguarding

Principles of Contextual Safeguarding

- Collaborative: Collaborating with professionals, children and young people, families and communities to inform decisions about safety.

- Ecological: Considering the links between the spaces where young people experience harm and how these are shaped by inequalities.

- Rights-based: Rooted in children’s and human rights.

- Strengths-based: Building on the strengths of individuals and communities to achieve change.

- Evidence-informed: Producing research that is grounded in the reality of how life happens. Proposing solutions informed by lived experience.

|

ECPAT UK: On the Safe Side: Principles for the safe accommodation of child victims of trafficking

ECPAT UK has identified that there are no commonly agreed safety and protection standards across the UK for the placement of children who are suspected or known to be trafficked. This inconsistency has allowed safeguarding issues to be side-lined and, in some instances, cast aside, leading to further harm to the child. In August 2009, in the light of these findings and to help support efforts to find safe accommodation options for child victims of trafficking, ECPAT UK relaunched its Three Small Steps campaign to protect child victims of trafficking. The campaign calls on the government and local authorities to ensure that these children are provided with safe and supported accommodation, preferably in the form of foster carers who have been trained in caring for child victims of trafficking. |

As part of this campaign, ECPAT UK explored the issues around what makes accommodation safe for child victims of trafficking by undertaking structured face-to-face interviews and a roundtable discussion with a range of professionals, including local authority children’s services, the police, NGOs and organisations accommodating child victims of trafficking, as well as ascertaining the views of the young people themselves. This led to the formulation of 10 child-centred principles concerning the provision of safe accommodation for child victims and/or suspected child victims of trafficking.

Just for Kids Law is a UK charity that works with and for children and young people to hold those with power to account and fight for wider reform by providing legal representation and advice, direct advocacy and support, and campaigning to ensure children and young people in the UK have their legal rights and entitlements respected and promoted, and their voices heard and valued.

They have youth advocates who can:

- Come to meetings with you and help you to express your wishes and feelings

- Speak to or email other professionals for you

- Help you understand your rights

- Explain your different options so you can make a choice about what you want to do

- Explain legal processes so you understand what is happening

- Put you in touch with lawyers or other advice or support services

The Scottish Guardianship Service for unaccompanied and separated children In Scotland, the Guardianship Service for children allocates a guardian for each unaccompanied, asylum-seeking child who can provides independent advocacy, advice and support on welfare, immigration, asylum and NRM procedures. Any local authority or agency in Scotland can make a referral to the Scottish Guardianship Service.The service was awarded the 2016 Children’s Champion award by ECPAT (Every Child Protected Against Trafficking) in recognition of the service’s child-centred model of practice with unaccompanied, separated and trafficked children in Scotland.

The Guardianship Service has developed from initially three guardians supporting approximately 30-45 new children each year to 15 guardians supporting 165 new children each year, with an average caseload of about 300 children and young people. The service has continued to innovate, by introducing complimentary services and projects to support young people’s needs. For example, in addition to the legal service provision, it has introduced a befriending service as well as mental health peer support for young men. All children have their own tailored integration plan in the guardianship service.

The service continuously feeds into, and updates the integrated children’s plan which is supervised by social work services as part of the national GIRFEC (Getting it Right for Every Child) policy. GIRFEC ensures child-centred assessment and care management as part of the multi-agency response to child welfare in Scotland from initial contact to recovery and integration which under the Scottish legislation can continue up until the age of 26.